Federal Election Toolkit

First Nations and Youth Action

This toolkit is a resource to empower First Nations communities and young people with the knowledge and confidence to participate in the electoral process. It offers practical resources on voting, community organising, and influencing policy, aiming to break down systemic barriers and support informed, meaningful participation in shaping the future.

This toolkit is a resource to empower First Nations communities and young people with the knowledge and confidence to participate in the electoral process. It is mainly a curated compilation of links to the work of other organisations covering two main areas, the practicalities of the voting system itself, and how to organise and mobilise your community to influence policy and the election results. Where we saw a gap in the information, we have included some of FYA’s own resources.

Many First Nations people face systemic barriers to voting, including logistical challenges, mis and disinformation, and a lack of culturally appropriate engagement. By equipping individuals and communities with this toolkit, we aim to empower young people to take action on issues that matter to them, increase voter participation, ensure informed decision-making, and strengthen First Nations representation in government.

For young people, including those who may be voting for the first time, this toolkit is designed to be a resource to enable informed participation. Voting is an opportunity to shape the future you will inherit. Youth participation in elections strengthens broader advocacy efforts and ensures that issues important to younger generations—such as climate action, education, housing, poverty and justice reform—are considered in political decision-making.

A note on terminology regarding First Nations communities throughout this toolkit – many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people prefer to be known by their distinct and diverse nations, clans and tribes. When referring to the collective, we prioritise terms like First Nations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and colloquial terms like ‘mob’ over the term ‘Indigenous’ which has been co-opted by all levels of government.

For young people, elections provide an opportunity to bring attention to issues that matter most to them, such as the climate crisis, mental health services, and affordable housing. Voting allows young people to influence who makes decisions on their behalf and hold leaders accountable for their promises.

For First Nations communities, engaging in the political process both during and outside election campaigns can be a step toward self-determination and addressing systemic inequalities. Historically, First Nations people fought for the right to vote, with full voting rights across all jurisdictions achieved only in 1965. Recognising this history highlights the importance of exercising this right and continuing the push for fair and just representation in government policies. By voting and/or engaging with candidates and communities during elections, both young people and First Nations communities can contribute to meaningful change and ensure that their voices are heard in shaping a more inclusive, just and equitable future.

However, racism continues to play out in Federal politics in many ways, both overtly and systemically, with devastating impacts. From the very violent colonial foundations of Western ‘democracy’ in so-called Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-white voices have been historically ignored, oppressed and excluded. For this reason, some people within First Nations communities refuse to engage with the colonial political system at all, highlighting how this system prioritises symbolic change that largely limits the rights and autonomy of First Nations peoples (read Tony Birch’s thinking on the politics of refusal here or the case of an Elder refusing to recognise a colonial court).

Any citizen of Australia over the age of 18 must vote in a Federal Election if validly enrolled and not disqualified from voting or overseas. Enrolling to vote requires adding your name and address to the electoral roll. This is the list of voters entitled to vote in an election. You can enrol from when you’re 17 years old, so you’re ready to vote after your 18th birthday. The electoral roll closes on April 7, so make sure you don’t miss out! If you don’t vote and you’re eligible, you’ll be issued a fine.

As a voter you have the right to accessibility and assistance in order to vote.

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) offers translated information in a variety of languages and formats to help everyone understand enrolling and voting in Australia. The AEC also offers options for people who are blind and have low vision and an Easy Read format that’s designed to make reading accessible to individuals with diverse cognitive disabilities, low literacy levels, or those who may face challenges in comprehending complex information.

If you can’t get to a polling place on election day you can vote at an early voting or mobile voting centre or apply for a postal vote.

Information for people with disability and mobility restrictions

If you need assistance to vote at a polling place, you can ask someone to help you. Polling place staff are trained to assist you or you can nominate any person (other than a candidate) to assist.

A list of polling places will be made available on the AEC website in the weeks after an election is announced. Each polling place is given an accessibility rating to assist people with disabilities or mobility restrictions. These ratings are:

As the election approaches, it’s important for all eligible voters, regardless of their circumstances, to understand their rights. Unfortunately, there are myths and misinformation surrounding the voting process that could deter eligible voters from having their say.

Even without a fixed address people can still vote in Australian elections. The AEC recognises that many people may not have a fixed address, such as those who are homeless or moving frequently. If you don’t have a fixed address, use this form to enrol to vote.

You are restricted from voting only if you are currently serving a full-time sentence of more than three years, a restriction identified as a human rights concern by the Australian Human Rights Commission. Australian citizens aged 18 and over who have served their sentence are entitled to vote, including people on parole and those with prior convictions. Prisoners must be enrolled and remain enrolled while they are serving a full-time prison sentence. Serving a full-time sentence does not include at-home detention, a Community Corrections Order or parole. In those cases, they can enrol and vote as an ordinary voter. You can enrol to vote as a prisoner here.

Australia has strict protections for the privacy and secrecy of votes. When you vote in a Federal Election, your vote is completely anonymous unless you choose to tell people how you voted. The design of the Australian voting system ensures that no one can identify how an individual voted. The act of casting your vote is secret, and there are strict rules around the handling of ballots. The only thing that identifies a voter is their name on the electoral roll, which is separate from their actual vote.

If there’s a circumstance in which having your address included in the publicly available electoral roll puts you or your family’s safety at risk, then you are able to apply to be a silent elector.

The voting system is imperfect, and as a result it means not all people enjoy the same access to voting due to discrimination or inaccessibility. If this occurs you can make a complaint or provide feedback directly to AEC.

If you wish to use an external complaint mechanism you can also contact:

If you are an Australian citizen aged 18 and above, you are required by law to register (“enrol”) to vote. If you are not registered to vote (“on the electoral roll”) then you can do so from now up until April 7.

You can enrol to vote online via this website. You can also enrol by filling out a paper form which you can download here, pickup at AEC offices; state/territory electoral offices; or you can contact the AEC and they will send you one. There are specific forms for those with no fixed address or serving a sentence (of less than three years) in prison.

For more information see the Electoral Commission’s easy English guide. Scroll down for other languages.

If you have moved house or changed your name since you enrolled, you can update your details via the enrolment form (just choose the option to update your details). You can do this at any time up until the electoral role closes seven days after the election date is called.

You can check your current details via this website.

Voting in Australia is compulsory.

There are several different ways to vote. No matter how you vote, it will be counted the same.

Most people will vote in person on the day of the election. You can also vote in person before the election or vote by mail (called “postal voting”). You can apply for a postal vote once the election is called, and you need to send it back before the day of the election. People with a disability or mobility restrictions can get assistance to vote (see how here), including telephone voting for blind and low-vision voters.

See the easy English guides on how to vote in person and how to vote by mail for more information. Scroll to the bottom of these docs for the phone number to the translation service if you’d like the information in another language.

If you live in a residential care facility, a remote location, homeless shelter or prison, a mobile polling station may visit you. You will need to contact the Australian Electoral Commission to find out where their mobile polling stations are going.

Australian Federal Elections have a preferential voting system, which requires you rank the candidates in order of your preference across two ballot papers (House of Representatives and Senate). This system is an Australian invention that ensures voters’ views on multiple candidates are taken into account, so you can still have a say in who represents you, even if your top choice doesn’t win.

See the Australian Electoral Commission’s guide on how to make sure your vote counts. You must number all the boxes on the House of Representatives ballot paper, and at least 6 above the line or 12 below the line on the Senate ballot paper. The more you number on the Senate paper (above or below the line), the more likely your vote is to count all the way until all the Senators are elected.

While it is a little mathematical, understanding our voting system is empowering!

Check out these resources to build your understanding:

Our voting system is different to that in other countries like the USA and UK which use “first past the post” (you just vote for one candidate without any preferencing). Our preferential system means that you can vote for a minor party or independent as your first preference, while still voting for the major party of your choice via your preferences (if your number 1 candidate doesn’t win). False claims that voting for minor parties or independents “splits the progressive vote” or “wastes your vote”, are representing what happens in other countries, but not in Australia.

The most important thing to know about preferences is they are up to you! You do not need to follow any candidate’s or organisation’s how-to-vote card. Sometimes, parties and candidates do preference deals and their how-to-vote card may not reflect the values of their voters.

It’s a good idea to do some research before you go to vote (see Section 4). To vote, start by choosing the party or candidate you support the most (or dislike the least!) and put them number 1. Then number sequentially from most to least liked. See the Australian Electoral Commission’s guide on how to make sure your vote counts.

Your vote will help elect one House of Representatives member for your local area, and six (if you live in a state) or two (if you live in a territory) Senators. To form a government requires a majority of seats (76 or more seats) in the House of Representatives. If no single party gets a majority (a ‘hung parliament’) they will need support from a number of other members, most likely from a minor party like the Greens and/or independents. When a major party needs your vote to either block or pass legislation this is described as having the ‘balance of power’.

You must number all the boxes on the House of Representatives ballot paper, and at least 6 above the line or 12 below the line on the Senate ballot paper. The more you number on the Senate paper (above or below the line), the more likely your vote is to count all the way until all the Senators are elected.

There are tools out there to help you prepare your preferences such as Build a Ballot (will be live once ballot papers are finalised), and the ABC’s Vote Compass can help you see how your views align with the main political parties’ policies.

If you do decide to follow a how-to-vote card, make sure you trust the candidate or organisation it has come from, and make sure it is in line with voting rules.

Comparing the policies of parties and candidates is crucial for informed voting. They impact many aspects of our lives including education, jobs, healthcare, First Nations rights and climate action.

Imagine two political parties have different plans for education.

By comparing their policies, young people can decide which party better supports their access to education and future job opportunities.

Policy scorecards break down party commitments in a simple, easy-to-compare format. They are often created by advocacy organisations that are focused on that particular policy area. It’s important you check who has created the scorecard you are looking at, and whether they are a trustworthy source of information.

Here are some examples from the 2022 and 2025 Federal Election:

Between elections, how do you know that the individual speaking for you, in your electorate, votes in your interest? Does their voting record reflect your values and those of your neighbours? Do they even turn up?

The They Vote For You website is a useful resource to peel back the layers of stuffy jargon, arcane procedures and language and find out how your MP voted on, for example, expanding powers to intercept communications or for Aboriginal land rights.

It’s easy to get started by searching or head to the full list of Representatives and Senators. It is likely that your current representatives will run again. If so, you can judge them on their record. Please note that this website is not always up to date.

Specifically on the issue of Gaza, Muslim Votes Matter has set up an MP tracker.

We encourage you to think about issues you care about, and turn them into questions for candidates so you can see where they stand. Short on ideas? Here are some questions taken from active youth-led and youth-focused campaigns. Their answers may help inform your vote.

First Nations Rights & Self-Determination:

GetUp: Will you commit to fully funding and implementing First Nations-led solutions for treaty and truth-telling?

Education & Employment:

National Union of Students: Will you lower the age of independence for Centrelink to 18 and increase the Youth Allowance rate so students aren’t forced to live in poverty?

Young Workers Centre: Will you ban discriminatory junior wage rates?

Justice & Legal System Reform:

Raise the Age: Will you support raising the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 and ending systemic racism in the justice system?

Youth Representation & Civic Engagement:

Make it 16: Will you commit to extending voting rights to 16 and 17 year olds?

Housing:

Renters and Housing Union: Will you build sufficient public housing to end the public housing wait list?

Climate Action & Environmental Protection:

Seed: Will you end all public money handouts to coal, oil and gas corporations and instead invest those funds in First Nations communities-led climate solutions?

Australian Youth Climate Coalition: Will you ban unconventional fossil gas extraction (fracking) in the Northern Territory?

Before you set out to campaign around the election, take a moment to work out what your strategy is by answering some key questions:

Shifting votes is hard work. Often to have an impact on an election you need to be campaigning for many months, sometimes years, before the actual election date. Elections are a powerful moment to push for the change you want to see in the world, but just as important is the work you do between elections. That being said, see below for some information and inspiration for hitting the streets, internet and airwaves!

If you want to dig deeper into the thinking behind engaging in elections (or not) see this article.

For inspiration, check out some of the work done in the lead up to previous elections by the Australian Youth Climate Coalition and School Strike for Climate.

If you want to know more about what your current member of parliament or the other candidates stand for, or you have an issue that you want to make sure candidates understand, then reach out to them and ask for a meeting!

Not sure how to do that? Check out the meet your candidate guide by the Australian Youth Affairs Coalition for steps and advice (note this guide is from 2022 so some information may be outdated).

Democracy in Colour has created an anti-racist candidate pledge – just fill out the form and they will ask candidates in your electorate to sign up to a pledge to get racism out of politics.. You can also sign this petition from Democracy in Colour calling for politicians to stop engaging in scapegoating of communities.

For an example check out the Multicultural Youth Advocacy Network’s engagement with MPs and Senators in the lead up to the 2019 Federal Election.

If you want to ensure that your issue is part of the election debate, then you can run a local information session and invite candidates to attend, or run a candidates forum where local candidates can present their policies on the issue to voters. Here are some tips for running a candidate forum (note, this is a resource from the USA, for local tips, see below).

Tips on running an information session, event or candidate forum

For inspiration check out the Victorian Aboriginal community event held in the electorate of Cooper in 2019.

A policy scorecard is another way to communicate to voters how the different parties and candidates perform on the issue or issues you care about. Check out some example scorecards from the 2022 Federal Election:

Note that if you print out scorecards or any other materials related to the election, you may need to “authorise” them. This usually involves having the name and address of a person involved in making the material included on it. See the AEC for more information.

Door knocking is a good way to directly engage in meaningful conversations with people and win hearts and minds. To do some doorknocking you’ll need a group of people, a script, some maps, an information pamphlet and a friendly and curious attitude. Check out the Nature Conservation Council of NSW for a local how-to doorknock guide. You can also check out this guide prepared by the international Blueprints for Change group. Check out which youth-led groups are doing door-knocking this election and join in to see how they do it!

A commonly used racist tactic in media and politics is referred to as a “dogwhistle”. According to the Cambridge dictionary, a dogwhistle is “a remark, speech, advertisement, etc. by a politician that is intended to be understood by a particular group, especially one with feelings of racism or hatred, without actually expressing these feelings.”

Dogwhistling is used to some extent by all political parties and media outlets, as these narratives are embedded into Australian identity, patriotism and media. So it’s important to learn how to recognise them, fact check and analyse them to form your own view on the issue.

Some examples:

If you want to gain a deeper understanding about how to shift racist media narratives and counter racist dogwhistling, look at these actions and resources from Democracy in Colour:

If you want to learn about how to frame your message in this election – whether it be for social media, public speeches or conversations with family and friends – here are a few handy resources to look at.

Passing the Message Stick is a groundbreaking multi-year First Nations-led research project designed to shift public narrative in support of First Nations justice and self-determination, launched by Australian Progress and GetUp in 2021. This report identifies 7 recommendations for messaging:

Passing the Message Stick also made a Messaging 101 guide that outlines the ‘VVVV’ messaging structure:

Example of the VVVV messaging structure from GetUp social media post:

If you want to gain a deeper understanding of deficit discourse and strengths-based approaches, read this summary report on deficit discourse by the Lowitja Institute (Australia’s only national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled health research institute).

‘Deficit discourse’ refers to disempowering patterns of thought, language and practice that represent people in terms of deficiencies and failures. It particularly refers to discourse that places responsibility for problems with the affected individuals or communities, overlooking the larger socio-economic structures in which they are embedded.’ – Lowitja Institute

Social media can be a powerful tool for advocacy. Here are some ways to use social media effectively during the election:

The media can be a very effective method for spreading awareness of issues or campaigns in the lead-up to an election. Engaging with ‘traditional’ media (such as written articles, radio interviews, and television segments) can be used to amplify your message or put pressure on decision-makers at a time when a lot of people will be watching what they say, and figuring out who to vote for.

It’s important to make sure that you feel safe, comfortable, and prepared before speaking to a journalist – and for any interviews you give or information you pass on to be on your terms and for your own purposes. The FYA Youth Media Centre has put together a resource pack with some helpful guides on how to prepare for interviews, hold a press conference, and pitch to the media, as well as templates to get you started for writing your own media releases and opinion pieces.

During the weeks leading up to the federal election, journalists will be looking for stories on issues important to voters – this is a great opportunity to ‘surf the wave’ of increased attention, but it also means the media landscape is quite saturated. It’s a frenzied time, and this means journalists are very busy, and lots of people and groups will be vying for attention. Be patient, think carefully about what is most important to you and your community, and don’t be discouraged if someone says ‘no thanks’ to a story you’d like covered. Your voice and lived experience is valuable, and remember – the media is just one tool in your toolbelt! Your hard work and advocacy does not begin and end with media coverage.

If you would like any extra support, advice, or help liaising with the media during the lead-up to the federal election, the Youth Media Centre is available. You can reach out to FYA’s Youth Media Lead, Heather McNab, at youthmedia@fya.org.au

Tips and checklists for getting media interest in your issue, knowing your rights when speaking to journalists and how to prepare for an interview:

If you want to connect with First Nations media specifically, below are a few useful contacts and links:

If you want to pitch a story to any media outlet and want more contacts and advice, get in touch with Heather at the Youth Media Centre: youthmedia@fya.org.au

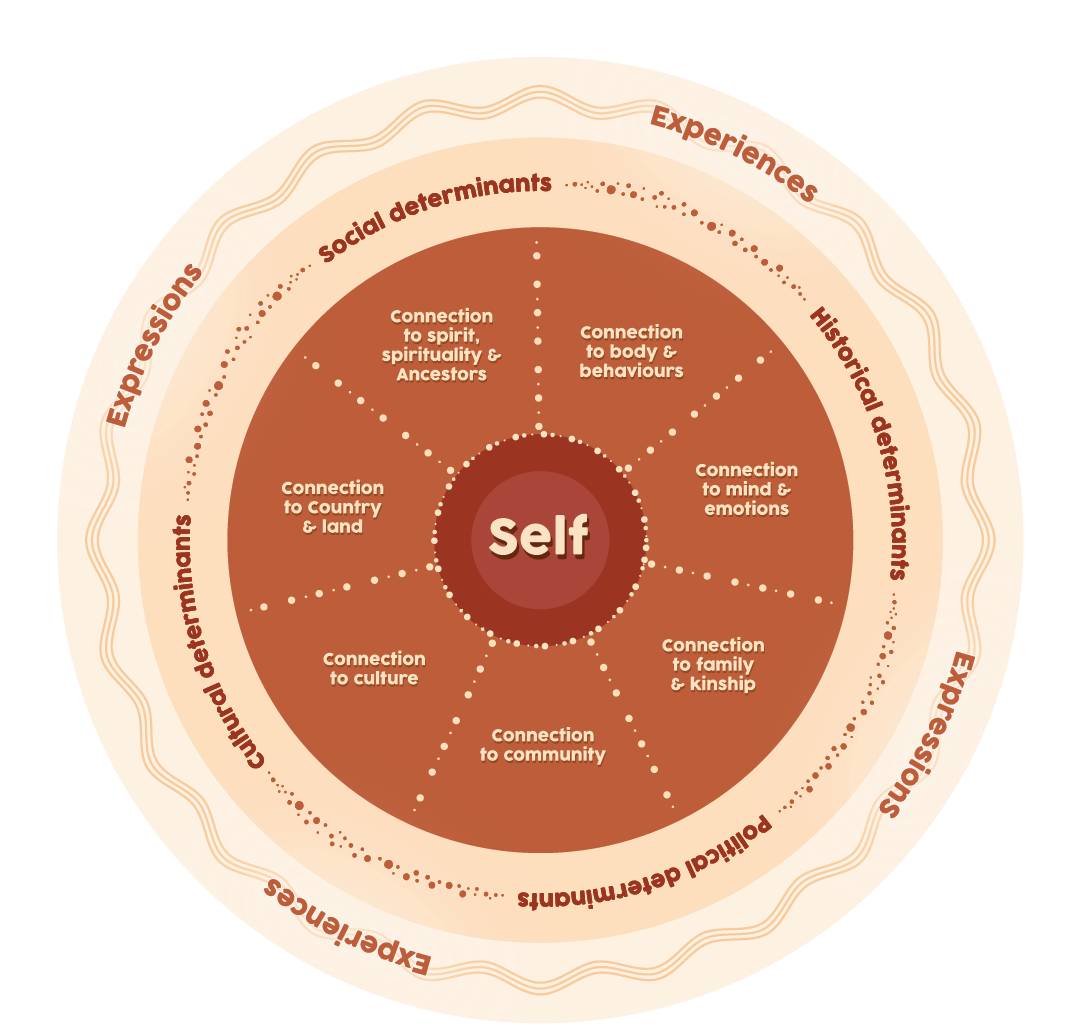

Participating in elections—whether by voting, advocating for your community, or engaging in political discussions—can be empowering but also emotionally and mentally demanding. Prioritising your wellbeing ensures you can stay engaged in ways that feel sustainable and meaningful. When thinking about wellbeing it’s important to consider social and emotional wellbeing (see below diagram), which is a strength-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health discourse which is recognised across Australia (and internationally) as culturally unique and community created. Strong and dynamic relationships between the seven domains enables individuals, families, and communities to thrive.

SEWB diagram from Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) Fact Sheet

If the electoral process or political discussions impact your mental health, consider reaching out:

Your voice matters, and so does your wellbeing. Taking care of yourself ensures you can continue advocating for your community in a way that feels sustainable and empowering.

Access to reliable information and support is essential for informed voting and active community engagement. Below are key resources to assist with voter enrolment, understanding the electoral process, and organising community initiatives.

FYA acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we all work and live. We recognise their continuing connection to land, water and community and pay respects to Elders past, present and those yet to come. We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded. This always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

Authorised by Foundation for Young Australians, Melbourne.

This resource was compiled by the Foundation for Young Australians in 2025. All external content linked or referenced remains the property of its respective owners.